In their attempt to clarify exactly what could be considered the ‘classical Hollywood style’ up to 1960, David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson have proposed that “causality, consequence, psychological motivations, the drive toward overcoming obstacles and achieving goals” form the basic premise of the standard Hollywood story, with “character-centred – ie. personal or psychological – causality” being the “armature of the classical story”. Hollywood was the great powerhouse in film production, making it an obvious reference point from which to compare and contrast the cinematic style of Antonioni. These critics expand on their preliminary argument for the central role of characters in driving film narrative, specifying that:

“a character is made a consistent bundle of a few salient traits, which usually depend upon the character’s narrative function. It is the business of the film’s exposition to acquaint us with these traits and to establish their consistency.”

This is clearly a standardised form to which Antonioni’s films do not conform. The characters in the films in question certainly were not the clearly constructed and predictable entities that audiences had perhaps become subconsciously conditioned to expect. Antonioni does not indulge in a gentle gradual process of character development; as Seymour Chatman has argued, “His characters come to us already fully formed, already totally in their situation”. This is not to say that they appear ‘complete’, for it is precisely their ‘incompleteness’ and ‘impenetrability’, which demand the viewer’s attention.

In Antonioni’s films, there is notable exclusion of indulgent character building, a trait exemplified in the opening sequence of L’Avventura. Here there is a pointed exclusion of the establishing shot that is so often employed by Hollywood directors to set the scene, to establish the filmic world that they have created and wish for the audience to invest in emotionally. Following the credits, there is a simple fade in that immediately puts the viewer face to face with Anna, walking purposefully towards the camera (Fig.1). Only when her torso fills the frame does the camera become mobile and begin to track back, wishing to keep her in frame but forced to concede to her determined approach (Fig.2). This tracking shot continues until Anna pauses, now in a close-up, having come to the end of the driveway, as she looks for the source of two voices, revealed to be those of her father and a local workman (Fig.3). The submissive but attentive backward motion of the camera as Anna advances is almost like a visualised acceptance of the absolute actuality of this character. Following that initial fade in, the viewer continues to anticipate a cut that will serve, slightly belatedly, to contextualise Anna, to establish her surroundings or perhaps explain the reason for her determined advance. But the viewer is left wanting. Antonioni reveals that this is all that will be divulged of her formation up to this point, that this present surface reality is as much as we will know about Anna, and, as soon becomes apparent, as much as we will know about any of the characters.

However, one effect of this stylistic choice is that identity is, to some extent, decomplexified. We are asked as viewers to accept the characters on surface value only, overlooking the formative complexities of their past or even their situation immediately preceding their appearance on screen. It is this concept that gives way to what Peter Brunette has called “visual doubling”, a technique that, he argues, serves to “augment the films’ depiction of subjectivity or identity as something fluid and contradictory”. In this he refers to the phenomenon of character reinvention that features most explicitly in The Passenger, as the film deals with David Locke’s discovery of a dead man in an adjacent hotel room and his assuming of this man, David Robertson’s, identity. After he first discovers the dead body sprawled face down on the bed, the identity exchange is somewhat foreshadowed. Having turned Robertson onto his back, Locke sits down next to him and at one point, leans right down so that his face is only inches away from the lifeless face of the corpse (Fig.4). As Locke examines Robertson’s suitcase, the camera repositions, framing Locke’s hands as he looks through the dead man’s things, pulling out his passport and an aeroplane ticket (Fig.5). His head still outside the frame, Locke is seen hovering over Robertson’s clothes before he reaches down and pulls out a gun, turning it over in his hand. At this point the camera does not tilt upwards to register Locke’s reaction but instead there is a sudden swift cut to a similarly focused shot that awkwardly frames Locke’s head and shoulders right at the bottom of the screen (Figs.6&7). It is as if, through the editing of the sequence, Antonioni is hinting at a separation of Locke from himself, with this refusal to show his head and body together in one shot. The viewer next sees Locke adopt a certain superficial likeness to Robertson, donning a blue shirt of his, something that occurs off camera. The subsequent scene sees Antonioni address what could be dubbed ‘bureaucratic identity’. Peter Brunette has highlighted the emphasis that is placed on the forging of Locke/Robertson’s passport, arguing that:

“…the passport is the largely artificial, if bureaucratically efficient way in which governments unsuccessfully attempt to name and fix human identity. The very title of the film, in Italian, “Professione: Reporter”, is reminiscent of a space on a passport that is meant to assist this effort to say just who we are. (Its curious linguistic hybridity adds to the sense of the complex artificiality of the resulting construct.)”

In this sequence we literally see Locke re-construct his identity. Taking a sharp razor blade to his headshot he patiently and meticulously peels his physical surface identity away from his bureaucratic identity and superimposes it onto another. And just like that, for all official intents and purposes, he ‘becomes’ David Robertson and David Locke ‘becomes’ the dead man. This smooth exchange directly problematizes Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson’s theory on the nature of typical characterisation, as a mere half hour into the film the protagonist rejects his own identity and adopts that of a subsidiary character. This exchange may not finish as Locke hoped but his desperation to separate himself from his self and the simplicity of the action with which he is able to do it, is not portrayed as liberation but rather a commentary on the precariousness of identity.

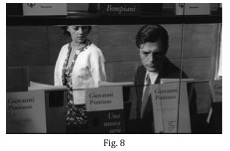

While Antonioni does explore this more transient and unsettled side to identity, he also tackles a concept of identity at the opposite end of the scale. As well as those characters that appear dislocated and lacking this “consistent bundle of a few salient traits”, there are also those who seem to be conceived as ‘absolute’ characters. Within Antonioni’s films of the early 1960s, such characters feature in both La Notte and L’Eclisse in the form of ‘professionals’. Giovanni Pontani, the up-and-coming writer who appears in La Notte, and Piero, the young and wealthy stockbroker from L’Eclisse, are prime examples of such characters. La Notte follows Giovanni and his wife Lidia on the day of the launch of his new book, and then at a lavish party thrown by a local businessman. The viewer often sees Giovanni framed by books, one such occasion being when he and his wife arrive at his book launch, the camera watching them through an open-shelved glass wall. Copies of Giovanni’s book, proudly bearing his name in large bold print, cover the shelves visible in the foreground, cluttering the lower part of the screen. As he approaches the door, Giovanni pauses, his head tightly, almost oppressively, framed by shelves laden with his books. Shot in a medium close-up, Giovanni, his name and his works dominate the screen (Fig.8). But this is not a glorifying shot. There is no look of triumph on his face as he pauses to survey the shelves and a rather disinterested looking Lidia continues a few steps ahead before she even realises he has stopped. William Arrowsmith has picked up on this, arguing:

“Again and again the films shows us Giovanni’s life-in-death, the image of him, caged among his books, is that of a mummy surrounded by a wall of dusty scrolls and files in which he has been buried alive.”

With only his face left unobscured by the books, Giovanni is presented to the viewer as nothing more than a face and a name, just the surface image of an author, a man trapped inside his profession.

This is much the same in the case of Alain Delon’s Piero, the stockbroker in L’Eclisse. Delon’s good looks and star presence instantly mark him out as the film’s male protagonist and yet, for a lead, he is strangely unlikeable. Antonioni makes no effort to endear the character to his audience, leading Peter Brunette to argue that, “Antonioni is playing an interesting, risky game here with the viewer’s attraction/repulsion to this central character, so obviously a product of the times”. Antonioni himself said of Piero in an interview in Theatre Arts that, “…this man is locked up in his world of investments, speculations. He is lost in the convulsive activity of the market. The market governs his every action, even his way of loving”. The viewer meets Piero in his natural habitat, the Bourse in the centre of Rome. The first thing the camera shows him do is position himself slyly behind two fellow stockbrokers who are exchanging tips in hushed tones. The slight high angle of the shot confers a certain sense of judgement, of disapproval. Having eavesdropped, Piero immediately acts on this confidential information and is thrilled when he comes away from his transaction a million better off. This ‘do anything to get ahead’ mentality also manifests itself in the way Piero behaves and moves around the Bourse, treating it like his own personal playground. There is certainly plenty of hustle and bustle but whenever Piero enters a group of people, he is always the first to grab shoulders, push people aside, raise himself up on his toes, shouting and gesticulating aggressively. When later in the film his car is stolen by a drunk and then discovered the next day crashed in a nearby lake, the drunk – now dead – still behind the wheel, Piero’s main concern is not for this lost life but for the money it will cost him to have his beloved car repaired or replaced. Everything he does and feels is driven by money and it is this unrelenting and unhealthy obsession that Antonioni seems to critique. Such characters are just as much “a product of the times” as those discussed previously who seem unable to hold down and embody a single fixed identity. Through his focus on these two extremes, Antonioni highlights the glaring absence of a happy middle ground, an absence of characters who are consistent and who have an apparent “personal or psychological causality” that would allow them to fulfil a conventional narrative function.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Antonioni, Michelangelo. 1962 About Nothing – With Precision (Theatre Arts 46, No. 7)

Arrowsmith, William. 1995. Antonioni: The Poet of Images (Oxford University Press)

Bordwell, D., Staiger, J. and Thompson, K. 1988 Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960 (Routledge)

Brunette, Peter. 1998. The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge University Press)

Chatman, Seymour. 1985. Antonioni; Or, the Surface of the World (University of California Press)

STILLS FROM

Antonioni, Michelangelo. 1960. L’Avventura (Cine del Duca, 1960. Mr Bongo Films)

Antonioni, Michelangelo. 1960. La Notte (Movietime 1961. Eureka Video 2008)

Antonioni, Michelangelo. 1975. The Passenger (Proteus Films, Inc. Sony Pictures Classics)